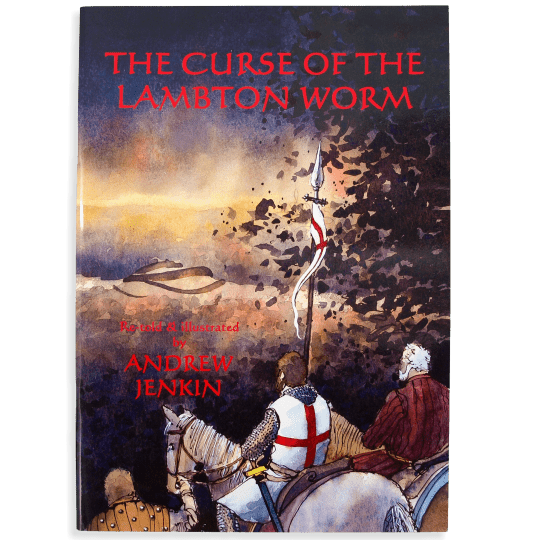

Huddersfield based artist Andrew Jenkin, who has roots in the North East, has taken the story of the Lambton Worm and transformed it into an original work, both re-writing the story itself and also painting the accompanying watercolour illustrations.

With a B.A.(Hons) in History and Ancient History, Andrew has also used his expertise in carrying out extensive research into the background to the legend and has brought together into one book many of the theories on why the legend may have arisen, the historic background and locations mentioned in the legend, together with a detailed map of the relevant area, has produced a family tree of the early Lambton family, and discusses the tale’s influence on later stories, plays and local culture. Some of the ideas mentioned in the book are expanded in more detail on this website.

Illustration from the Book, ‘The Curse of the Lambton Worm’

“…Drawing his sword, he resolutely turned to face the vile creature that he had inflicted upon his village. The Worm slowly unwound itself from the rock and slid into the river…”

The legend tells of young John Lambton, son of a noble family in County Durham, who was fishing in the River Wear on a Sunday. When he was unable to catch a fish, he cursed the river, and immediately hooked an ugly little black worm which he later disposed of, in disgust, in the local well. This worm was to grow into a great serpent-like monster which blighted Lambton village and wreaked havoc in the area whilst John was away fighting in the Crusades for seven years.

When he returned home, now Sir John, he learned about the terrible creature that he had inflicted upon his village, and in remorse, set out to combat this monster. With the advice of a wise woman, he devised a suit of armour strong enough to withstand the power of the serpent and covered with spikes to penetrate its scales.

He successfully killed it, but in so doing inadvertently inflicted a curse upon his own family which was to last for nine generations.

The legend of the Lambton Worm is believed to date from the 14th century, and the earliest published version of the legend was by Robert Surtees, the well-known Durham historian who recorded the traditional oral version of the legend as recounted by Elizabeth Cockburn of Offerton. Surtees later included the legend in the second volume of his work ‘History and Antiquities of the County Palatine of Durham’ published in 1820.

The draft version for this had been read and corrected by Sir John George Lambton, later 1st Earl of Durham, so we know that Surtees published that version of the Lambton Worm legend with the authority of the Lambton family. Sir John Lambton, reputedly the hero of the story, was a real person who became a Knight of Rhodes, and the book ‘The Curse of the Lambton Worm’ gives details of his place in the Lambton family tree.

There are many versions of the legend of the Lambton Worm, believed to be from the 15th century. Some of the later versions describe the Lambton Worm as a creature with a salamander-like head and nine holes on either side of its mouth; the salamander is unique amongst vertebrates in that it can regenerate lost limbs and other body parts.

It is uncertain where the origin of this came from, and it may have merely been a flight of fancy on the part of the story-teller. If we are to take Surtees’ account as the definitive version, he merely describes the young Worm as a “small worm or eft” (young eel) and the description may have become embellished over the years. © Andrew Jenkin 2009

Worm Well

Worm Hill

Robert Surtees was born in 1779 at Mainsforth, Durham. . He studied law at Christ Church, Oxford, but without being called to the bar, he returned to the family estate at Mainsforth, which he inherited on his father Robert’s death in 1802, and where he lived for the rest of his life. He devoted himself to the study of local history and antiquities, and to collecting material for his ‘History and antiquities of the County Palatine of Durham’ which was published in four volumes from 1816 until the last in 1840, after the author’s death.

The work contains a large amount of genealogical and antiquarian information; written in a humorous and readable style. Surtees was also a talented ballad writer, and so successfully imitated the style of old ballads that he even managed to deceive Sir Walter Scott, who included a piece by Surtees called “The Death of Featherstonehaugh” in his Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border, under the impression that it was ancient. In 1807 Surtees married Anne Robinson of Herrington, and he died at Mainsforth on the 11th of February 1834; he is buried at Bishop Middleham. As a memorial to him the “Surtees Society” was founded in 1834 with the purpose of publishing ancient unedited manuscripts relevant to the history of Durham County.

In “The Curse of the Lambton Worm”, a possible connection between the legend of the Lambton Worm to a 14th century legend about the Dragon of Rhodes is mentioned. Sir John Lambton, as a Knight of Rhodes himself, would have been fully aware of the legend and would no doubt have recounted the story on his return to England. The legend of the Dragon of Rhodes, and details of the Order of the Knights of Rhodes is expanded below:

The Order of the Knights of Rhodes was founded from the Order of St. John, or the Hospitallers, which was an order of sworn brethren which had arisen at the time of the first Crusades. The Order of St John was begun in Jerusalem by monks who assisted penniless pilgrims who arrived at the city by not only feeding and housing them, but also doing their best to cure the many diseases that they caught on the journey. The Hospitallers obtained permission from the Pope to become warriors as well as monks so that they could further the Christian cause in Jerusalem. They were thus all in one – knights, priests, and nurses; and their monasteries became both castles and hospitals; where the sick pilgrim or wounded Crusader was sure of medical care, and, if he recovered, an escort to safety.

Around 1309 the island of Rhodes became home to this Order, and they became known as the Knights of Rhodes, in existence until 1522.

A few years after the Order of the Knights of Rhodes was founded on the island, Rhodes was ravaged by an enormous creature living in a swamp at the foot of Mount St. Stephen, about two miles from the city of Rhodes. It devoured sheep and cattle when they came to the water to drink, and even young shepherd boys went missing. Known locally as a dragon, it has been suggested that a crocodile or serpent might have been brought over by storms or currents from Africa, which could have grown to a formidable size unnoticed among the marshes, or grown with the re-telling of the story! Pilgrims visiting the Chapel of St. Stephen, on the hill above its lair, put their lives at risk as it was rumoured that they may be devoured by the dragon before they could climb the hill.

Several brave knights had tried to kill the creature, but the dragon was said to have been covered with impenetrable scales and all had perished in the attempt. At last the Grand Master, Helion de Villeneuve, forbade any further attempts to kill the creature.

A young French knight, however, named Dieudonné de Goza (also known as de Gozo or de Gozon), who had seen the creature but had never managed to attack it, was unwilling to give up. He requested leave of absence, returned to his father’s castle in Languedoc, and had a model made of the monster. He had noticed that the creature’s belly was unprotected by scales, but was impossible to reach due to its huge teeth and lashing tail. He made the stomach of his model hollow and filled it with food, then trained two fierce young mastiffs to attack the underside of the monster, while he earfuld attacking the monster from above, mounted on his warhorse.

When he was satisfied that the horse and dogs were trained, he returned to Rhodes, landing in a remote part of the island for fear of being prevented from carrying out his plan. Having prayed at the chapel of St. Stephen, he left his two French squires, instructing them to return home if he were slain, but to watch and come to him if he killed the dragon, or was injured by it. He then rode down the hill towards the haunt of the dragon. It roused itself as he came, and at first he charged it with his lance, which was useless against the scales. His horse was quick to notice the difference between the true and the false monster, and reared up, so that Dieudonne was forced to leap to the ground and was knocked down by the monster’s lashing tail; but the two dogs attacked the creature as they had been trained, and the knight, regaining his feet, plunged his sword into the creature. When the servants finally arrived, they found the knight lying apparently dead under the carcass of the dragon, but they managed to revive him and brought him into the city amid the ecstatic shouts of the whole populace, who conducted him in triumph to the palace of the Grand Master.

There was, however, a great moral to be learnt from this tale – which was probably recounted to all the succeeding probationary Knights of Rhodes, including Sir John Lambton – for despite praising the knight for his brave actions, the Grand Master, Villeneuve, was angry with his disobedience and dismissed him from the Order. As he pointed out, the discipline of the Order of Rhodes was humility and implicit obedience to the Grand Master, and Dieudonné had broken this vow and followed his own self-will. Dieudonné was, however, eventually reinstated, and the dragon’s head was set up over the gate of the city, where historians allegedly saw it even in the seventeenth century, describing it as larger than that of a horse, with a huge mouth and teeth and very large eyes. Dieudonné de Goza was elected to the Grand Mastership after the death of Villeneuve in 1346, and was reputed to be a great soldier, much loved by all the poor peasants of the island, to whom he was exceedingly kind. He died in 1353, and his tomb is said to have been inscribed with these words:

“Here lies the Dragon Slayer.”

Much of the enduring fame of the Lambton Worm is owed to the song which was written for the pantomime version of ‘The Lambton Worm’ in 1867 by C.M.Leumane, and which has been adopted as a folk song. The pantomime was first performed at Tyne Theatre and Opera House in Newcastle-upon-Tyne. The lyrics and music are shown below:

One Sunday morn young Lambton Went a-fishin’ in the Wear;

An’ catched a fish upon his huek He thowt leuk’t varry queer, But whatt’n a kind a fish it was

Young Lambton cudden’t tell.

He waddn’t fash to carry’t hyem So he hoyed it doon a well.

(Chorus)

Whisht! Lads, haad yor gobs, An Aa’ll tell ye aall an aaful story,

Whisht! Lads, haad yor gobs,

An’ Aa’ll tell ye ‘bout the Worm.

Noo Lambton felt inclined to gan

An’ fight in foreign wars.

He joined a troop o’ Knights that cared

For neither wounds nor scars, An’ off he went to Palestine

Where queer things him befell,

An’ varry seun forgot aboot

The queer worm I’ the well.

(Chorus)

But the worm got fat an’ growed an’ growed,

An’ growed an aaful size;

He’d greet big teeth, a greet big gob,

An’ greet big goggle eyes.

An’ when at neets he craaled aboot

To pick up bits o’news,

If he felt dry upon the road,

He milked a dozen coos.

(Chorus)

This earful worm wad often feed

On calves an’ lambs an’ sheep,

An’ swally little bairns alive

When they laid doon to sleep.

An’ when he’d eaten aal he cud

An’ he had had he’s fill,

He craaled away an’ lapped his tail

Seven times roond Pensher Hill.

(Chorus)

The news of this most aaful worm

An’ his queer gannins on

Seun crossed the seas, gat to the ears

Of brave an’ bowld Sir John.

So hyem he cam an’ catched the beast

An’ cut ‘im in twe halves,

An’ that seun stopped he’s eatin’ bairns,

An’ sheep an’ lambs and calves

(Chorus)

So noo ye knaa hoo aall the folks

On byeth sides of the Wear

Lost lots o’ sheep an’ lots o’ sleep

An’ lived in mortal feor.

So let’s hev one to brave Sir John

That kept the bairns frae harm

Saved coos an’ calves by myekin’ halves

O’ the famis Lambton Worm

(Chorus)

Noo lads, Aa’ll haad me gob,

That’s aall Aa knaa aboot the story

Of Sir John’s clivvor job

Wi’ the aaful Lambton Worm!

This website and all subject matter, artwork and imagery it contains are the exclusive property of Andrew Jenkin. All materials on this website, including images and artwork, are owned and controlled by Andrew Jenkin and may not be copied, reproduced or republished in any way. All artwork on this site and the images contained therein have been produced by Andrew Jenkin.

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |